“Men were the hunters and women were the gatherers.”

This statement has become a common and unquestionable fact within our society, but does it hold any validity? Modern Homo sapiens have been on this planet for an estimated 315,000 years [1], and only began farming and building housing during the Neolithic Revolution in the Middle East’s Fertile Crescent around 12,000 years ago [2]. But what of those 303,000 years? What were we doing then? While this article will not delve into all aspects of those 303,000 years, it will examine the hunter-gatherer period of human history and the effect gender had on communal roles. By looking at the origin of the male-hunter/female-gatherer theory, modern research, biological factors, and common sense, it is easy to see how ridiculous our presumption of this history really is.

Man: The Hunter

To understand how society accepted this theory as fact, we have to look at where it started. The theory of men as hunters and women as gatherers is relatively new, emerging in the late 1960s. Much of the support for this idea came from the 1966 symposium Man the Hunter, organized by Richard Lee and Irven DeVore. What is particularly striking about this symposium is that it became one of the most influential theories of hunter-gatherer societies, despite being grounded primarily on assumptions rather than in statistical or genetic evidence. Moreover, it is essential to note that this piece’s main point wasn’t even about men being hunters and women being gatherers, but rather about how hunting and gathering created community for humans.

The assumption was that, because male biological tendencies make men stronger and faster, men did the hunting. This theory went virtually unchallenged for sixty years—whenever human remains were found with weapons, they were assumed to be male. Robert Kelly [3], a professor of anthropology at the University of Wyoming, stated to NPR [4], “No one,” Kelly said, “had done a systematic tally of what the observational reports said about women hunting.”

Modern Findings

Although feminists have questioned the notion of men doing all the hunting for decades, it wasn’t until 2020 that there was a solid attempt from the scientific community to test who did the hunting and who did the gathering. So, fifty-four years after the fact, Cara Wall-Scheffler, backed by the University of Washington and Seattle Pacific University, set out to test if hunting and gathering were based on sex.

Wall-Scheffler and her colleagues studied accounts of prehistoric hunting methods dating back to the 1800s and beyond. This led Wall-Scheffler to discover that, rather than the presumed sex-based system, prehistoric societies were much more relaxed about gendered roles, with 79% of societies having female hunters [5]. Furthermore, the study found that women didn’t just participate in opportunistic or small-game hunts. Wall-Scheffler reported to NPR that “the hunting was purposeful. Women had their own toolkit. They had favorite weapons. Grandmas were the best hunters of the village.”

Effects on Modern Society

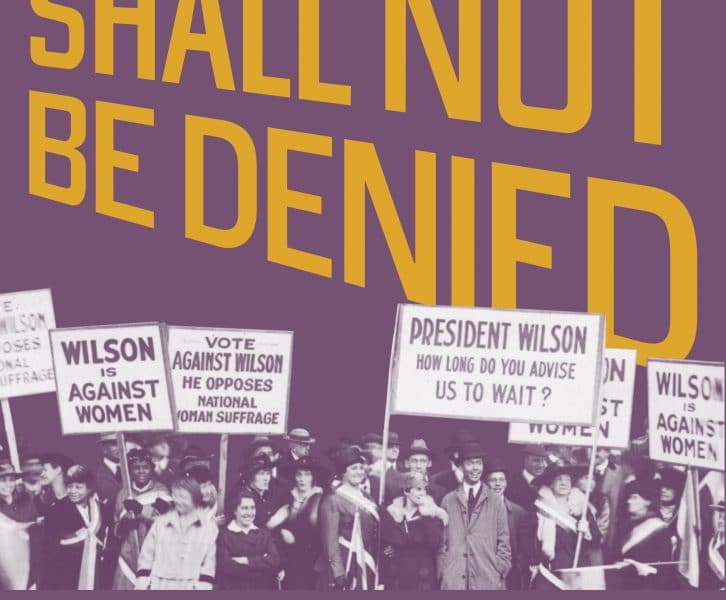

So, how does a nearly sixty-year-old theory about our million-year past affect today? The idea that men were hunters feeds the argument that men are natural breadwinners and providers, justifying jobs and positions of power being given exclusively to men. It’s important to recognize that this theory was popularized during the second wave of feminism and by those who sought to push back against change. During this time, it wasn’t uncommon for people to believe that men had natural intellectual superiority over women, so when this theory justified men’s supposed physical prowess, it made them appear naturally better in nearly every category. By making women docile gatherers and reducing their natural role to being mothers, it internalizes the idea of the supposed inferiority of the female sex.

Be the Hunter

The fact of the matter is that women are not primarily created to be mothers to men or to serve a lifelong supportive role to them. We have been given the ability to be hunters, chiefs, and whatever else we want to be. Although this theory has been used to justify the subordination of the female sex, it is debunked daily. Be the hunter you were meant to be.

_____________________________________________________________________________

Side note: Below, I have pasted some links that go into more detail about this part of our history. I cannot recommend these articles enough:

Prehistoric hunters weren’t all male. Women killed big game, new discovery suggests | CNN

Men are hunters, women are gatherers. That was the assumption. A new study upends it.

________________________________________________________________________

Citations

Rafferty, John P. “Just How Old Is Homo sapiens?” Encyclopaedia Britannica, Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2017, https://www.britannica.com/story/just-how-old-is-homo-sapiens.

HISTORY.com Editors. “Hunter-Gatherers.” History, A&E Television Networks, 5 Jan. 2018, updated 28 May 2025, https://www.history.com/articles/hunter-gatherers. HISTORY+1

Kelly, Robert L. “Robert Kelly — Emeriti Faculty.” Department of Anthropology, University of Wyoming, University of Wyoming,

https://www.uwyo.edu/anthropology/personnel/emeriti-faculty/er-kelly.html

Aizenman, Nurith. “Men Are Hunters, Women Are Gatherers. That Was the Assumption. A New Study Upends It.” NPR, 1 July 2023, https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2023/07/01/1184749528/men-are-hunters-women-are-gatherers-that-was-the-assumption-a-new-study-upends-i.

Anderson, Abigail, Sophia Chilczuk, Kaylie Nelson, Roxanne Ruther, and Cara Wall-Scheffler. “The Myth of Man the Hunter: Women’s Contribution to the Hunt across Ethnographic Contexts.” PLOS ONE, vol. 18, no. 6, 2023, e0287101.

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0287101